Abstract

The Foundations of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic until 2035 refers to the Northern Sea Route as Russia's ‘national transport communication’ but not all countries agree with this wording. This article uses the positions of Russia, some Arctic (Norway, the United States) and non-Arctic (China) countries as examples to show the full range of interests of various players with regard to the future development of the Northern Sea Route. .

Keywords: international relations, Arctic, Arctic states, international transport corridor, Northern Sea Route, Northeast passage, Russia, Norway, USA, China.

Introduction

Interest in the Arctic and its resources has been growing steadily in recent years, both on the part of traditional Arctic powers and non-regional players. This is not surprising: according to scientists, the Arctic is home to vast undiscovered reserves of natural resources, and the region itself occupies a strategic position with considerable logistical potential. Two major transport corridors pass through the Arctic: the Northwest Passage and the Northeast Passage. The main part of the latter is the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a shipping route in the Russian Arctic. It is currently the focus of attention both in Russia and abroad: the Northwest Passage, which runs in the territorial waters and exclusive economic zone of Denmark (Greenland), Canada and the United States, is blocked by ice for most of the year and has a much shorter navigation period than the NSR.

The NSR: a Russian or an International Transport Corridor?

The NSR is the shortest route between European Russia and the Far East. It runs through the seas of the Arctic and Pacific Oceans from the Kara Gates1 to Provideniya Bay2. The total length of the NSR in this section is approximately 5,600 km, so this route is almost twice as short as other sea routes from Europe to the Far East [3].

Currently, the NSR transports mainly fuel and energy raw materials and equipment for field development and infrastructure construction. The NSR’s cargo turnover in 2014-2019 increased almost eightfold: from 4 to 31.5 million tons per year [13]. The growth has been particularly rapid in the last two years, partly due to an increase in the volume of liquefied natural gas shipments at the port of Sabetta (the Yamal Peninsula).

The Russian merchant shipping law defines the boundaries of the NSR water area [4, art. 5.1]. But despite the fact that the NSR runs in the territorial waters and exclusive economic zone of Russia, its development has various international aspects: the route attracts the attention of many regional and non-regional players.

Further in the article, the full palette of interests of various players with regard to the development of the NSR will be shown, using the positions of Russia, some Arctic (Norway, the USA) and non-Arctic (China) states as examples.

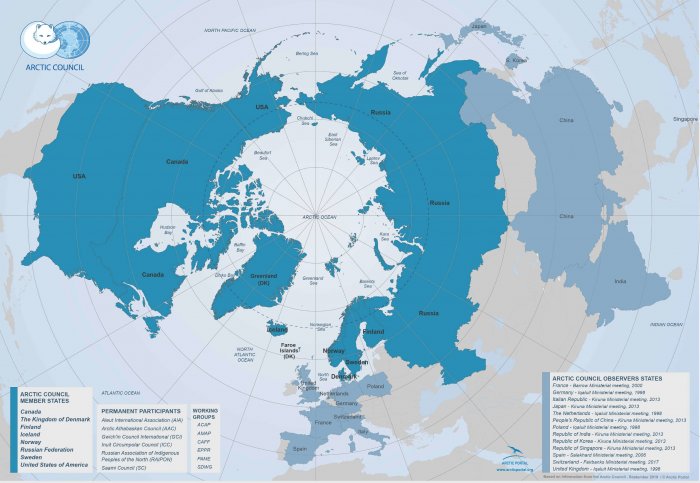

Pic.1. The Northern Sea Route map. Source: ‘Gekon’ consulting center..

Russia’s ‘National Thruway’

In the previous version of the Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone of Russia (hereinafter – the AZRF), the NSR was designated as ‘Russia's historically established national single transport communication in the Arctic’ [5] which is the baseline of the Russian approach.

The Arctic is a strategically important region for Russia: accounting for about 18% of the total area of Russia, it generates 11% of its national income, accounts for 22% of Russian exports, and produces about 80% of its natural gas and 60% of its oil reserves [10]. The development of the Arctic is impossible without adequate infrastructure, especially the transport one. Russian authorities attach great importance to the NSR, because land and air transport routes in the AZRF are underdeveloped.

In 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin set the goal of increasing NSR’s cargo turnover up to 80 million tons by 2024. The COVID-19 pandemic has made its adjustments: there are cautious statements now about the need to lower this target.

The main reason for the expected reduction in NSR’s cargo turnover is the drop in demand for energy resources caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The impact is ambivalent: on the one hand, the reduced demand has led to lower production and fewer resources to be transported. On the other hand, the decreased demand has meant that large-scale Arctic development projects have temporarily lost their economic viability.

A number of companies have already announced to postpone the launch of new production and refining capacities. Experts interviewed by Rossiyskaya Gazeta believe that with the recovery of demand for energy resources in the mid-term perspective the Northern Sea Route will be able to meet the targets again. In such case, the volume of cargo traffic will have reached 120 million tons by 2030 and 180 million tons – by 2035 [14].

Three main aspects determining Russia's position on the NSR can be distinguished: the military, economic and energy ones.

The Arctic, due to its geographical position, is a strategically important region for Russia in terms of ensuring national security in its broadest sense. The development of the NSR will increase the transport accessibility of the Russian North – and increase the mobility and efficiency of the armed forces units deployed in the AZRF.

Economically, the NSR is the main transport route in the North, linking the remote territories of the AZRF and often being the only way for them to deliver goods. Moreover, the NSR is part of the larger international Northeast Passage. With proper development and appropriate investment in infrastructure3 , it can compete with the key maritime ITCs linking Europe and Asia via the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca, which can significantly strengthen Russia's international maritime transport market position.

Finally, the energy aspect lies in significant reserves of natural resources – mainly hydrocarbons – which, once extracted, need to be brought onshore, transported to other parts of the country and then exported to foreign markets. In this context, the NSR appears to be the main logistical artery for energy resources in northern latitudes. The NSR is already one of the main transportation routes for Russian LNG (Yamal LNG).

Thus, Russia 1) considers the NSR a national transport corridor and develops respective national legislation based on the international maritime law4 ; 2) is actively developing infrastructure along the entire route to gradually increase cargo turnover and transform the NSR into one of the leading ITCs.

However, many other countries do not share this ‘national approach’ of Russia and actively criticise the development of the NSR. In the following sections we will examine their positions in detail.

Pic.2. The port of Sabetta, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. Source: «Malamut-Trans» LLP.

Crouching U.S., Hidden Norway

Other regional players are reserved about the idea of developing the NSR, and some openly criticise the Russian approach to transport route management. For example, for Canada and Denmark, the NSR is a competitor to the Northwest Passage, although using the latter as an ITC is a matter of a very distant future.

Norway, for instance, takes a neutral and wait-and-see approach to the NSR and at the official level declares the project to be economically inexpedient while raising the issue of its compliance with environmental standards [8]. Foreign Minister I.M. Eriksen Søreide in an interview with Izvestiya said that ‘the NSR had serious problems with everything from search and rescue operations and insufficient infrastructure along the entire route to the extremely harsh climate’ [11].

The United States, on the opposite, has strongly criticised the project and challenged Russia's right to manage the NSR, demanding freedom of navigation along the entire route. U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo, speaking at the Arctic Council summit in Rovaniemi, called the navigation regime established by Russia on the NSR illegal. He noted the deep concern of the U.S. over ‘Russia's claims to international waters of the NSR, including plans to align the route with China's Maritime Silk Road project’ [9].

Such a U.S. approach is understandable: over the past decades, Washington has shown little interest in Arctic policy, has not invested in the development of an icebreaker fleet – and has fallen significantly behind in terms of developing the Arctic [7]. Against the backdrop of Russia's growing activity on the NSR and the gradual increase of China's presence in the region, the United States seeks to preserve its position, questioning the legitimacy of Russia's actions and trying to create an appropriate image in the eyes of the world community. Such a rhetoric resonates: some major American and European companies have already refused to use the NSR as a container transportation route. Russian authorities attributed it to ‘Russia's leading position in the Arctic basin’ and the lack of other states’ developing capacities in the North, including a nuclear-powered icebreaker fleet [12]. Under these circumstances, Trump's proposal to buy Greenland from Denmark does not seem so absurd: the island occupies a critical position.

Рис.3. From left, Norwegian Foreign Minister Ine Marie Eriksen Soreide, Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Sweden's Foreign Minister Margot Wallstrom and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stand for a group photo, during the Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting in Rovaniemi, Finnish Lapland, Tuesday, May 7, 2019. Source: Vesa Moilanen/Lehtikuva via AP.

China and ‘The Polar Silk Road’

Non-Arctic states, especially those in East and Southeast Asia, have been increasingly interested in the NSR. For them, the NSR is an attractive alternative route for supplying products to European markets. The most active player here is China, which is increasingly asserting its Arctic ambitions and is even positioning itself as a 'near-Arctic state'.

In 2018, the Chinese government outlined the basic principles and objectives of country's Arctic policy in a white paper. With regard to the NSR, which is referred to in the document as the Northeast Passage, China, without challenging the jurisdiction of the respective countries in the Arctic waters5 , states the need for free navigation along the entire route [6]. Beijing has even set the task of aligning the NSR with the Belt and Road project and is already proposing to develop it as ‘The Polar Silk Road’ [6].

Such a position has provoked strong criticism on the part of some Arctic states, most notably the United States, which is concerned about China's excessive strengthening in the region. Nevertheless, some researchers think that this policy is dictated by purely commercial considerations and appears to be very cautious so far [2]. Moreover, China's proposals on joint development of the NSR fit into the current logic of Moscow, which is interested in attracting foreign investment to develop the infrastructure of the transport artery provided that it retains control over the route. Some experts even call China ‘Russia's closest partner in the development of the NSR’ [1].

Рис.4. Hu Kaihong, a spokesman of State Council Information Office, shows China’s new Arctic Policy at a news conference on January 26, 2018 in Beijing, China. Source: CNBC.

Conclusion

The high level of interest in the NSR is defined by its potential as an alternative to the main maritime ITCs and the growing importance of the Arctic in international relations. For Russia, the development of the NSR is a strategic objective, without which it is impossible to strengthen its position as a leading Arctic power. Other regional players – for example, the United States – actively resist this development and contest Russia's right to manage the NSR. Non-Arctic countries are expected to advocate its free use, pursuing their own economic interests and seeking to establish themselves as regional players – as China does.

Thus, we can observe a clear clash of interests of various international players on the issue of the NSR development – both regional and non-regional ones – and it will depend on Russia's determination and persistence whether the NSR can one day become a full-fledged Russian alternative to other maritime ITCs.

1 It is generally accepted that the NSR begins at the Kara Gates, but sometimes the 'capital of the Russian Arctic' Murmansk is taken as the starting point and the entire route is divided into two sections: the Western and the Eastern ones.

2 Russia's Ministry for the Development of the Far East and Arctic has recently proposed almost doubling the boundaries of the NSR water area, from Murmansk to Sakhalin. See Sevmorpust’ [Electronic resource] // Kommersant [website]. – 21.05.2020. – URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4349939 (accessed on 28.12.2020).

3 Such attempts are already being made (see e.g. Northern Sea Route Infrastructure Development Plan 2035 [Electronic resource] // Russia’s Ministry for the Development of the Far East and Arctic [website]. – 30.12.2019. – URL: https://minvr.gov.ru/press-center/news/24164/?sphrase_id=1480825 (accessed on 28.12.2020)), although criticised by many Russian experts as clearly insufficient.

4 Further on the legal aspects of shipping on the NSR see RIAC Reader. The Northern Sea Route [Electronic resource] // The Russian International Affairs Council [website]. – URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/sevmorput (accessed on 28.12.2020).

5 Obviously, Russia is implied here.

References:

1. Zvorykina J., Teteryatnikov K. The Northern Sea Route as a Tool of Arctic Development // The Russian Economic Journal. – 2019. – N 4. – P. 21-44.

2. Moe A., Stokke O.S. China and Arctic shipping: Policies, interests and engagement // Kitaj v mirovoj i regional'noj politike. Istoriya i sovremennost'. – 2019. – №24. – URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/china-and-arctic-shipping-policies-interests-and-engagement (accessed on 28.12.2020).

3. Bol'shaya Sovetskaya enciklopediya [Electronic resource]. – URL: http://www.aggregateria.com/s/severnyj_morskoj_put.html (accessed on 28.12.2020).

4. Trade Shipping Code of the Russian Federation of 30.04.1999 N 81-ФЗ (ed. of 13.07.2020) // Sobranie zakonodatel'stva RF. – 03.05.1999. – N 18. – Art. 2207 (accessed on 28.12.2020).

5. Strategiya razvitiya Arkticheskoj zony Rossijskoj Federacii i obespecheniya nacional'noj bezopasnosti na period do 2020 goda [Electronic resource] // The Government of Russia [website]. – 2013. – URL: http://government.ru/info/18360/ (accessed on 28.12.2020).

6. China’s Arctic Policy White Paper [Electronic resource] // The State Council of the People’s Republic of China [website]. – 26.01.2018. – URL: http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm (accessed on 28.12.2020).

7. Is America losing out on the Northern Sea Route? [Electronic resource] // Raconteur Media [website]. – 10.09.2019. – URL: https://www.raconteur.net/global-business/usa/northern-sea-route/ (accessed on 28.12.2020).

8. Norway Has Doubts about Development of Russia’s Northern Sea Route [Electronic resource] // Russia Business Today [website]. – 26.08.2019. – URL: https://russiabusinesstoday.com/environment/norway-has-doubts-about-development-of-russias-northern-.... (accessed on 28.12.2020).

9. US Secretary of State calls Russia’s Arctic ambitions ‘illegal’ [Electronic resource] // Bellona [website]. – 07.05.2019. – URL: https://bellona.org/news/arctic/2019-05-us-secretary-of-state-calls-russias-arctic-ambitions-illegal (accessed on 28.12.2020).

10. Arktika. Infografika [Electronic resource] // Ministry for the Development of the Far East and the Arctic of the Russian Federation [website]. – URL: https://minvr.gov.ru/#gallery6 (accessed on 28.12.2020).

11. BezOslovno: Rossiya budet osvaivat' Sevmorput' bez uchastiya Norvegii [Electronic resource] // Izvestiya [website]. – 26.08.2019. – URL: https://iz.ru/912535/elnar-bainazarov/bezoslovno-rossiia-budet-osvaivat-sevmorput-bez-uchastiia-norv.... (accessed on 28.12.2020).

12. V RF ob"yasnili otkaz zapadnyh kompanij ot Severnogo morskogo puti [Electronic resource] // Sputnik Lithuania [website]. – 22.11.2019. – URL: https://lt.sputniknews.ru/russia/20191122/10727104/V-RF-obyasnili-otkaz-zapadnykh-kompaniy-ot-Severn.... (accessed on 28.12.2020).

13. Ob"em perevozok gruzov v akvatorii Severnogo morskogo puti [Electronic resource] // Edinaya mezhvedomstvennaya informacionno-statisticheskaya sistema (EMISS) [website]. – URL: https://www.fedstat.ru/indicator/51479 (accessed on 28.12.2020).

14. Ugol' sbrosil gruz [Electronic resource] // Rossijskaya gazeta [website]. – 30.08.2020. – URL: https://rg.ru/2020/08/30/plany-zagruzki-severnogo-morskogo-puti-mogut-byt-skorrektirovany.html (accessed on 28.12.2020).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY 4.0)